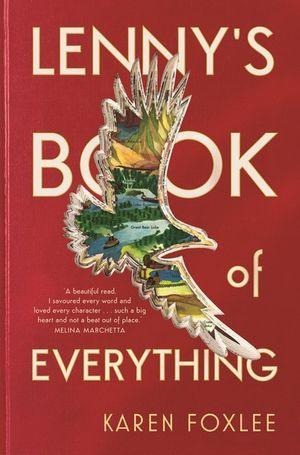

Karen Foxlee, Lenny’s Book of Everything, Allen & Unwin, October 2018, 352 pp., RRP $19.99 (pbk), ISBN 9781760528706

Lenny, small and sharp, has a younger brother Davey who won’t stop growing – at seven, he is as tall as a man. Raised by their mother, they have a roof over their heads but not much else. The bright spot every week is the arrival of the latest issue of Burrell’s Build-It-At-Home Encyclopaedia. Through the encyclopaedia, Lenny and Davey experience the wonders of the world – beetles, birds, quasars, quartz – and dream about a life of freedom and adventure. But as Davey’s health deteriorates,

Lenny realises that some wonders can’t be named.

Lenny’s Book of Everything is the latest book from award winning Australian author Karen Foxlee, and is a heartfelt tale of family, love, growing up and discovering the things that matter most in the

world.

The story is told in the first person, from the point of view of the titular character, Lenny, a fairly typical nine year-old girl. We see everything through her eyes and although the setting may not be familiar to most of us (ie, growing up in 1970s Ohio, USA), there are some aspects and elements of

childhood that seem to stand out as universal.

Foxlee’s prose is quite poetic and beautiful, and she captures the essence of a child’s experience of the world, how they view, savour and remember it. The details of how a person looks and smells, the “feel” of a person or place… Foxlee has expertly tapped in to the language of sensory memory,

which makes reading the book a very rich existential experience.

In terms of the target audience, I would hesitate to class this as children’s fiction, to be perfectly honest. It tackles some very intense subjects – loss, abandonment, serious illness, domestic violence, death – and while it’s all portrayed through the lens of a child’s understanding, it nevertheless presents the reader with a heck of a lot to process. I keep seeing this book in the “8-12 year-old” section of the bookshop, but I honestly wouldn’t give it to a kid younger than ten, and then only if they were extraordinarily mature emotionally.

Reviewed by Christian Price