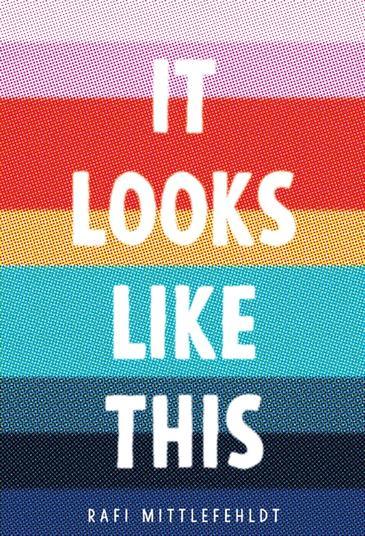

Rafi Mittlefehldt, It Looks Like This, Candlewick/Walker Books, Dec 2016, 336pp., $19.99 (hbk), ISBN: 9780763687199

It Looks Like This is an intense story of Mike, a repressed gay boy who is sent to conversion therapy in America when his religious father discovers him in a compromising situation with another boy, Sean. It happens quite late in the book. For almost the first half, we see Mike adjusting to a new high school, a closed minded art teacher, and a bully named Victor who watches his every move and attempts to rile him every chance he gets. Mike also meets Sean.

The tone is oppressive and claustrophobic. We know bad things will happen. They are foreshadowed and the inevitability increases tensions. Conversations in this story are written without quotation marks, keeping readers at a distance from Mike and the people with whom he interacts. His observations, and how much his father and Sean’s father, watch each son for clues, are sharp but confused. He is aware that they recognise something different in the boys. Sean and Mike’s attempts to fit in, to hide their true selves without even really understanding why, is cleverly depicted between the lines of everyday activity and conversation.

The only person on Mike’s side seems to be his younger sister Toby, portrayed as rebellious and smart. Her fearlessness is admirable, as is Mike’s desire to protect her. Ultimately, it is her support and protectiveness that keeps Mike strong, as well as the late realisation that other people are there for him. His mother is a silent blank canvas. That is, until the bad thing happens. That’s when she steps up.

This book and this dreadful occurrence are a timely reminder that we need to step in a lot sooner. Because we shouldn’t need bad things to happen before we implement changes to improve everyone’s life. It Looks Like This is all the more powerful for the quiet and controlled way it speaks about Mike’s situation. There is a growing number of LGBTQIA fiction books, and this one in particular doesn’t sit on the joyous and celebratory shelf, but rather the cautionary sad one. Of course, both representations are valid and necessary, as much as I wish the latter weren’t.

Reviewed by Trisha Buckley