Mem Fox was the 2017 recipient of the Nan Chauncy Award. This is the amazing acceptance speech she gave at the CBCA Book Week dinner in Hobart on 18 August. Her speech included a reading of her latest title, I’m Australian Too. There was lots of laughter, maybe even a few tears, as Mem held the audience spellbound. It’s a bit like “you had to be there”, but hopefully in reading this speech, you will feel some of the magic of that chilly Hobart night…

Good evening. Thank you. Thank you for this wonderful award. Thank you for your love and support over the years. Thank you for everything.

Before I go any further, I’d like to bow to the genius of my illustrators and kiss their feet. Without their talent, I would not be standing before you this evening. You will understand that picture book writers create only 50% of any successful picture book and artists do the rest, but the proportions of that creative partnership are too often ignored, so tonight I’d like to raise an Allelujah to illustrators everywhere.

I’d also like to bow to the many Australian authors of the past—none of whom is still alive, although their words live on in my heart—who endowed my childhood with exotic books about Australia, the country in which I was born: authors who explained the place, and explored it, and extolled it, and taught me to know and love it from afar, while I was growing up in Africa. Without them I wouldn’t be standing before you this evening.

Nan Chauncy was one of those authors. When I was about (!) twelve, in about 1958 (!) and beginning the I-love-horses phase of my life, Nan Chauncy was writing about wild brumbies and brave girls, the Australian bush, and racism, and Tasmanian Aborigines. I was living on a mission, predominantly with Africans, in what was then Southern Rhodesia and is now Zimbabwe, witnessing racism daily, and riding horses out in the bush, and being brave about snakes and speaking out about politics.

I came back to Australia in January 1970, with my very English husband. We were living here happily ever after—I was teaching drama in a Catholic girls’ school—when only four months after we arrived, in early May 1970, the news came though that Nan Chauncy had died. I had returned to the land she had made me love, and now she herself had left it. I felt selfishly sad, as if her work had belonged particularly to me.

So you can imagine my reaction when I was told that I’d been nominated for the Nan Chauncy Award! It was more than a feeling of being over the moon: it was a pent-up, lifelong, whoosh of gratitude to her, and all the other Australian authors I’d loved a child, who had nurtured me with so much care, and without whom I wouldn’t be standing here as the author of such one-eyed Australian books as Possum Magic, Wombat Divine, Hunwick’s Egg, Sail Away, Koala Lou, and I’m Australian Too.

My parents had generous friends back home who sent me and my sisters all the Australian books they could lay their hands on. My mother had a broad Sydney accent so her renditions of Blinky Bill, and Snugglepot and Cuddlepie made Australia a very real place to us. She also read us Banjo Paterson ballads, and CJ Dennis’s Songs of a Sentimental Bloke.

At this late stage in my life, a heartfelt tribute also to my mother, without whom Australian literature wouldn’t have entered my soul as deeply as it did.

Like many children living outside Australia, my sisters and I were riveted by Australian animals, a fascination enhanced by the long picture-story-books of Leslie Rees. My favourite of his was Shy, The Platypus. I loved it so much that in the late 80’s, when I was reading Walter McVitty’s book: Authors and Illustrators of Australian Children’s Books and discovered to my amazement that Leslie Rees was still alive and living at Balmoral Beach in Sydney, I wrote to him. I told him I’d adored his books and that his work had greatly influenced my becoming a writer. Unbelievably I was asked to dinner by this silver-haired god, who was 85 by then and still living alone. I did go to dinner with him, even though he lived in Sydney and I live in Adelaide. I confess I could hardly speak a sensible word. It was like an Elvis fan having dinner with Elvis.

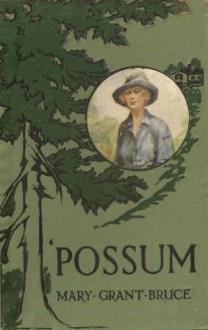

But the clearest memory of my childhood is curling up on my bed in the afternoons, while tropical storms slammed the roof, getting lost in fabulous novels by writers from an era long past: Mary Grant Bruce’s Billabong books, and Ethel Turner’s Seven Little Australians. This one was my favourite—this exact copy: Possum, by Mary Grant Bruce. [Hold it up.] Unbelievable, isn’t it? Possum, of all things.

But the clearest memory of my childhood is curling up on my bed in the afternoons, while tropical storms slammed the roof, getting lost in fabulous novels by writers from an era long past: Mary Grant Bruce’s Billabong books, and Ethel Turner’s Seven Little Australians. This one was my favourite—this exact copy: Possum, by Mary Grant Bruce. [Hold it up.] Unbelievable, isn’t it? Possum, of all things.

I don’t think I could have written a book as Australian as Possum Magic had I grown up here.

As an outsider, as the child of Australians who had made me feel that Australia was the closest place to heaven on earth, as the child of a mother who made lamingtons and pavlovas, who said, ’Stone the crows!’, and sang us: ‘On a track winding back to an old-fashioned shack/along the road to Gundagai…,’ as the child of a father who said he was feeling ‘cactus’ when he was feeling unwell, who called a pair of trousers ‘a pair of strides’, and who planted a grove of gum trees within months of arriving in Africa because he was homesick, I was probably more immersed in Australian culture, more aware of it, and more in love with it than most children in Australia at the time.

So you can imagine how puzzled I was, and then outraged, on my return in 1970, at the age of 22, to find Australia in the grip of something called ‘the cultural cringe.’ The population, by and large, was nowhere near being as proud of the country as I was. I couldn’t believe it. I was further outraged, a few years later, when I was able find only a few recent, decent Australian picture books for my own Australian child.

So, in 1978, when Felicity Hughes (without whom I would not be standing here today), a lecturer in children’s literature at Flinders University, told us that one of the requirements of her course was to write a children’s book, I set to in a fury to write the most Australian book possible. As history records, the story I wrote was the embryonic Possum Magic. Felicity gave me an excellent grade and encouraged me to find a publisher, which I tried to do.

But it (Possum Magic) was rejected nine times over five years, often by Australian publishers who said it was too Australian!

In my long list of tributes, therefore, I’d like to acknowledge yet again—and pay homage to Sue Williams and Jane Covernton of Omnibus Books in Adelaide, the tenth publisher to whom I’d send my manuscript, who believed in the potential of that early draft of Possum Magic back in 1982, and helped me create the much-loved story we all know today. I wouldn’t have been standing here had I not met them.

Sue and Jane, and everyone else behind the scenes of my books: editors like my American editor, Allyn Johnston, and Claire Hallifax and Laura Harris in Australia—in fact most editors, publishers, illustrators and art directors, are blocked from public view in the all hoopla over the author, but authors are only one cog in the wheel of a picture book, and we acknowldege that fact with humility.

Obviously, I’m overwhelmingly grateful to Julie Vivas, the illustrator of Possum Magic. a giant among illustrators, an absolute genius. I often wonder if the art in Possum Magic is what’s kept it alive for 34 years: its beauty has never dated, it’s magic has never dimmed. I certainly know I wouldn’t be standing here were it not for Julie. And also, would I still be standing here if it weren’t for Judy Horacek’s artwork in Where is the Green Sheep? I don’t think so. Or Jane Dyer’s art in Time for Bed? Or Helen Oxenbury’s pictures in Ten Little Fingers and Ten Little Toes? The list goes on and on and on, as does my deep gratitude.

Obviously, I’m overwhelmingly grateful to Julie Vivas, the illustrator of Possum Magic. a giant among illustrators, an absolute genius. I often wonder if the art in Possum Magic is what’s kept it alive for 34 years: its beauty has never dated, it’s magic has never dimmed. I certainly know I wouldn’t be standing here were it not for Julie. And also, would I still be standing here if it weren’t for Judy Horacek’s artwork in Where is the Green Sheep? I don’t think so. Or Jane Dyer’s art in Time for Bed? Or Helen Oxenbury’s pictures in Ten Little Fingers and Ten Little Toes? The list goes on and on and on, as does my deep gratitude.

I’m worried you might fall asleep, or start screaming if you hear these words again: ‘I wouldn’t be standing here if it were not for…’, so let me read you an Australian Mem Fox book, for a change. [Read I’m Australian Too.]

The highlights of my writing life, along with this award tonight, are the unexpected reactions I receive to individual books, such as the Aboriginal woman at the Savannah Festival in Townsville earlier this year, who stood up in a large audience and almost wept as she explained how moved she was by I’m Australian Too, because it was so astonishing and pleasing to have Indigenous people directly acknowledged as the first people who lived here.

And Natalia Swietlick, whom I met at a festival in Victoria in June, who told me she’d been a refugee from Poland in the early 80s and was now a vet.

‘That’s my page,’ she cried. ‘No one else can have it!’

And, moving to other books, there was the six-year-old in Texas, in a silent audience of hundreds, who, on hearing that Koala Lou hadn’t won the gumtree climbing event in spite of all her hopes and effort, pulled his face back in horror and called out: ‘Oh, Geez!’ And the seven-year-old boy in Wudinna, in South Australia, who asked if I were really the author of Possum Magic.

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘I am.’ And he said wearily: ‘I’m sick of Possum Magic.’

And then there was the heartbreaking story of two-year-old twins in the Adelaide hills who drowned in a water tank, and were laid to rest with a copy of Time for Bed. It had been their favourite book.

And then there was the wide-eyed eight-year-old boy in Maryborough at this year’s Mary Poppins Festival, who was sitting almost on my toes. I’d read only a couple of pages of Possum Magic when he breathed, ‘Oh, I LOVE this book.’ After reading Possum Magic so many times over 34 years, and realising it was still loved, I found myself so close to a sob I had to take a special breath myself, before I could continue.

Then there was the woman who had waited and waited till the end of a long evening and a long signing line, to tell me privately how much she loved Wombat Divine because her own son was Wombat.

Then there was the woman who had waited and waited till the end of a long evening and a long signing line, to tell me privately how much she loved Wombat Divine because her own son was Wombat.

‘He’s Down’s Syndrome,’ she said. And I said that as the author, I had known that Wombat was Down’s Syndrome, but I’d never spelled it out in the story. How had she known?

‘It was obvious,’ she said. And she started to cry.

You see before you this evening an elderly Mem Fox. But I’m not dead yet. My grandfather lived to be 96. I hope to be writing at 97, at least. But anyway, finally, a thousand invisible kisses to everyone at the Children’s Book Council for presenting me with the Nan Chauncy award this evening, and for recognising the literary efforts I have made over my current lifetime. The story continues.

The ending is not the end…

Mem Fox