What have the knights and ladies of the Twelfth Century got in common with the children in today’s schools? If we want to get our children reading, then the answer to this question is extremely important. Sean McMullen, (pictured far right in image on the left) tells us why.

Like modern children playing computer games, medieval knights played at war by fighting in tournaments. The ladies of the court sat in the stands and watched while their menfolk committed heroic acts of violence and stupidity in their honour. True, knights and spectators did get killed when things got out of hand, but as entertainment it was thought to be the best thing since gladiatorial combat was banned, seven hundred years earlier.

What was there to do in winter, when there were no tournaments? One could read a book, but in 1150 they were not a good deal. There were the chansons de geste (songs of deeds), but they were mainly about men fighting, and could be pretty tedious. I surveyed a few of them for my PhD. On average, women featured in just 3% of pages, and romance did not happen. Beowulf is an example, and even including Grendel’s mother, the gender balance is heavily skewed toward men.

Enter the roman courtoise (courtly romance), around 1160. The romans had a good balance between male and female characters, and romance was more important than the fighting, yet there was still plenty of exciting action. Magic was used more frequently, and it was an alluring new magic that inspired a sense of wonder. Knights could become werewolves or werehawks, rings could grant invisibility, and warriors could survive beheading. Most importantly, knights generally did great deeds for their ladies, not the crowned head who paid their wages. Romance and action had been brought together, just like in the tournaments. The catch was that you had to learn to read, but people did.

The roman courtoise caught on about as fast as the Internet did nine hundred and fifty years later. Marie de France and Chretien de Troyes were pioneer authors, and by 1200 it dominated European fiction. Real knights fought in tournaments as characters from romans, and some tournaments were presided over by real kings and queens dressed as Arthur and Guenevere. The chivalric behaviour described in books was adopted in real courts, especially the romantic bits.

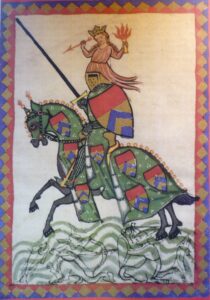

So, lots more people were reading, and their sharpened literacy skills were also applied to commerce, politics, religion, engineering and science. The invention of the printing press fed the demand for books, and the Middle Ages soon became the Renaissance. The church was not very happy about the amount of romance and violence in the new literature, but the expanded interest in reading did mean that more people could read religious books. Some knights, such as Walther von de Vogelweide (see image, left) and Ulrich von Lichtenstein (see image, right), even wrote their own romances.

So, lots more people were reading, and their sharpened literacy skills were also applied to commerce, politics, religion, engineering and science. The invention of the printing press fed the demand for books, and the Middle Ages soon became the Renaissance. The church was not very happy about the amount of romance and violence in the new literature, but the expanded interest in reading did mean that more people could read religious books. Some knights, such as Walther von de Vogelweide (see image, left) and Ulrich von Lichtenstein (see image, right), even wrote their own romances.

Now fast forward to the Twentieth Century. In my PhD research I found that, statistically, the factors that made the Twelfth Century roman courtoise so popular still appeared in most of the classic fantasy films and modern books that I surveyed (with Tolkein’s work being the notable exception). The conclusion is an obvious one. Fantasy literature is not vacuous escapism that wastes the time of young readers, it is a powerful tool that has lured people into opening books and improving their literacy skills for nearly a thousand years. It persuaded knights to put down their swords, get out of their armour and learn to read, so surely it can also persuade modern boys to put down their footballs and open a book. Marie de France pioneered a new type of fantasy at a time when female authors were unheard of, and I think she is a great role model for girls with aspirations to write.

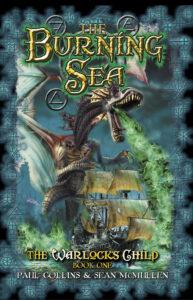

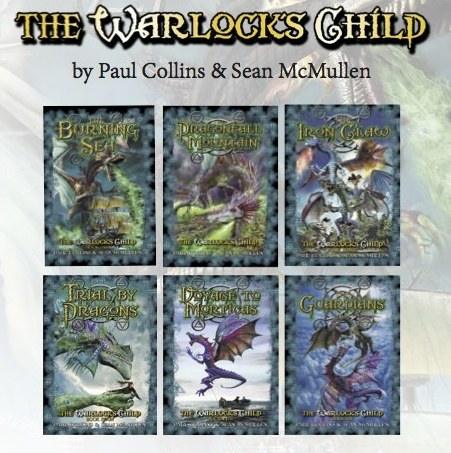

I had Marie de France in mind when Paul Collins and I were planning The Warlock’s Child fantasy series. Her collection of short lais were highly accessible to medieval reluctant readers, so we followed her model. Instead of a daunting hundred thousand word doorstopper, our story is spread over six much smaller books that are very approachable. The perspective is shared between the cabin boy Dantar and his sister Velza, providing the gender balance, and the series generally follows the guidelines of fast plot, action, romance and magic that revolutionized medieval recreational reading.

Today, as in the Middle Ages, the goal is to get students to open a book and sharpen their reading skills. Fantasy can do this, whether with knights or with footballers, and once they are reading, all the other benefits that literacy brings are already on the way.

The first book in the series, The Burning Sea, was published in April, followed by the second, Dragonfall Mountain, in May and the third, The Iron Claw published in June. The rest will follow.

Thank you Sean for such an enlightening article.