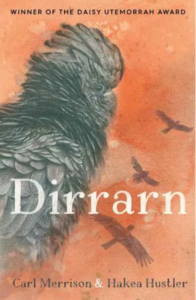

Merrison, Carl and Hakea Hustler (text) and Dub Leffler (illustrator), Dirrarn, Magabala Books, August 2023, 109 pp., RRP $17.99 (pbk), ISBN 9781922777027

Dirrarn is the Jaru word for the black cockatoo. The Jaru people are the traditional custodians of the lands of the East Kimberley region of Western Australia. The book is a sequel to the authors’ earlier book Black Cockatoo.

Mia, whom we first met in Black Cockatoo, has had to leave her country and travel far south to Perth to go to school. This means having to make major adjustments as she now has to wear a school uniform, comply with the school timetable, remember to do her homework and eat different sorts of food. She is now living in a city rather than the open spaces of the Kimberley and, because of all that, she feels very much an outsider.

She also has to deal with racism and bullying and, while it is not the first time she has encountered bullies, she does not really know how to deal with them in this new environment. She eventually finds the courage to tell her side of the story to the principal who understands her and the bully is moved from the school. Mia is a character with agency and strength as it takes bravery to make such a huge transition from her homeland to the school – even though she knows it is a privilege and she feels proud of herself for being the one from her community given that privilege, it is difficult for her.

Even in Perth things can remind her, and other First Nations girls, of Country. As they walk around Perth Zoo on an excursion, they encounter creatures that are their totems. Mia’s is the black cockatoo of the title. At the zoo too, Mia learns that there are agencies that look after and rehabilitate injured animals, something she has tried to do. She is determined to learn as much as she can about this.

Throughout the book there are language words, and the Indigenous girls speak to each other in Aboriginal English. This gives them a sense of belonging and solidarity, despite it also making them a target for the bullies.

Towards the end of the book when Mia returns home, we are privileged to read about some of the practices in Mia’s community. We also meet some of her family and understand their importance in her life. They, like all the characters in the book, even those who only make a brief appearance, are strongly drawn and help to give the reader a better understanding of Mia’s life, both at school and home.

The ending is slightly enigmatic – will Mia return to school after the holidays when she has felt so much happier and no longer homesick when she has returned to Country. There have been earlier hints that she will as she wonders if her new friend Naya will return with her, and her grandmother talks to her about her ability to excel in two worlds.

There is a glossary included in the back of the book that has a list of words in Jaru, aboriginal English, Kriol and Noongar with their English translations. The reader can go to the list to translate after finishing the story or while reading it. The context of the words in the story, however, usually makes their meaning clear. In this way, explaining to the reader that the name for black cockatoos is different for First Nations people in the north and south of Western Australia will make it clear to young readers , in a gentle way, that there were many different Indigenous languages.

Leffler’s beautiful black and white illustrations provide a visual introduction to each chapter and also interspersed throughout the written text.

Black Cockatoo won great acclaim and I feel sure that the sequel will too. It is a welcome addition to books for young people about First Nations children and their experiences.

Reviewed by Margot Hillel