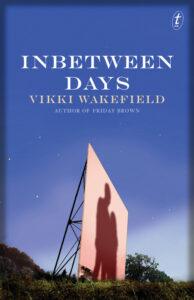

Vikki Wakefield’s third book has just been released. We asked her to tell us about writing it. Here is a lovely insight into her writing process, and the way she addressed the themes. Meet Vikki Wakefield.

Vikki Wakefield’s third book has just been released. We asked her to tell us about writing it. Here is a lovely insight into her writing process, and the way she addressed the themes. Meet Vikki Wakefield.

Recently I ran a workshop for emerging writers that focused on how to expand simple ideas into a more complex short story or novel. We worked through some exercises and I showed them the notebook I kept while I was writing Inbetween Days, my new novel, out in October. All of my notebooks are filled with drawings and vague notes, snippets of song lyrics, random scientific facts, pictures and paint colour-charts—seemingly unrelated stuff—but seeing the origins of Inbetween Days laid out like that made me realise that I do the opposite from what I’d been preaching.

Mine is not a process of building on an idea, but of breaking it down; I chisel away until I find clarity and a sense of inevitability. That’s when I know what the story is about.

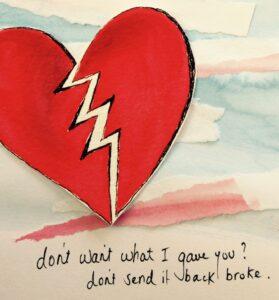

Inbetween Days began with a drive-in scene, a voice in my head, and the line, ‘The worst part was the waiting’. I can trace that line and one of the main themes of the novel back to a doodled sentence on the second page of my journal. It reads: wishing, waiting for life to begin; waiting and wishing—wasting. On the same page: I’m still haunted by the ghosts who broke my heart, and don’t want what I gave you? don’t send it back broke (which evolved into the funnier but less lyrical ‘love is a pie’ scenes in the book).

Inbetween Days began with a drive-in scene, a voice in my head, and the line, ‘The worst part was the waiting’. I can trace that line and one of the main themes of the novel back to a doodled sentence on the second page of my journal. It reads: wishing, waiting for life to begin; waiting and wishing—wasting. On the same page: I’m still haunted by the ghosts who broke my heart, and don’t want what I gave you? don’t send it back broke (which evolved into the funnier but less lyrical ‘love is a pie’ scenes in the book).

The book also grew from my obsession with Newton’s Cradle, the Möbius strip, and a pendulum wave. On the page the framework isn’t as obvious as many of the themes, but I used these ideas to build the town of Mobius (a place where people get stuck) and its history, the novel’s structure (the pendulum wave), and the plot and character interaction (Newton’s Cradle). Whenever I was lost, I’d watch YouTube videos of these experiments to find my rhythm again.

Jack’s story in Inbetween Days is an exploration of love and of the time between childhood and adulthood. Jack is sexually experienced but emotionally naive; she’s caught between her mother and her sister, and she must choose between two boys, Jeremiah and Luke, between holding on and letting go. She counts obsessively, to give herself the sense of being in control. Clocks tick, time passes, money runs out—but change is inevitable. Jack tries to reconcile her dreams and wishes with reality, and I used contrast—between life and death, youth and ageing, past and future, truth and lies, light and dark—to create a kind of limbo, not only for her, but for the other occupants of Mobius, too. As I wrote, I was always conscious of a pendulum, swinging (evidenced by a truly awful sketch of a Grandmother clock on page 11).

On another page I’ve pinned two portraits of a teenaged girl, taken a year apart. In the second portrait, her eyes are changed. I often wondered what she’d seen or experienced, so I wrote in past tense to compare the childishness of Jack’s immediate thoughts and actions with her more reflective narration of the story. As Jack loses the things she can quantify, she gains those that can’t be measured; as she grows and changes, her past and future voices converge.

The adults in Jack’s world make similar mistakes, and I’ve explored how some of the experiences that signpost the transition from childhood to adulthood are both universal and cyclical. Young people are in a hurry to grow up; the old dream of being young again. Growing up is made up of a million moments—not just one day, or one summer—and many of the choices Jack faces I took from my own experiences growing up. There are many displays of the in-between theme throughout the novel, some deliberate, a few accidental, but all were a side effect of breaking down those big ideas.

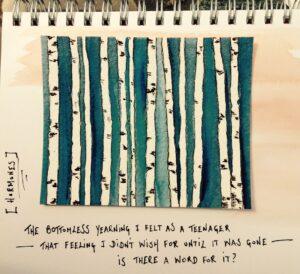

So now when I flick through my notebook, I see that the origins of Inbetween Days were never simple. On the second-to-last page I’ve written: the bottomless yearning I felt as a teenager—that feeling I didn’t wish for until it was gone—is there a word for it? I’ve scrawled hormones in the margin, but that’s a flippant answer. It’s a feeling more elusive than nostalgia, more acute than reminiscence—something I’m always chasing in my writing, whether it’s for young people or not-so-young people.

I’m not sure there is a single word for it. I’m still looking.