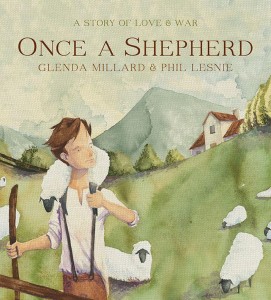

What’s it like to be asked to illustrate a book by one of your favourite children’s authors? Phil Lesnie gives us his reaction.

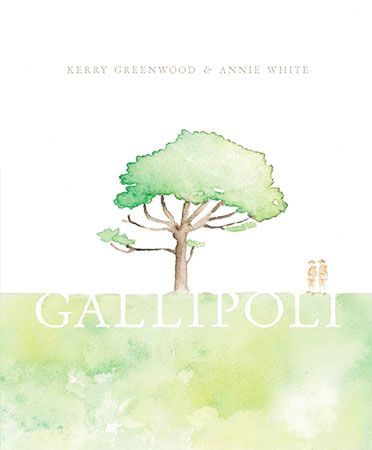

I think I should probably come clean about this, because it feels like it’s going to come up at some point – I actually don’t know the first thing about World War One. It’s almost obnoxious how rubbish I am as a student of history, given that I’ve been drawing and painting a particularly devastating part of it for the last year and a bit.

I won’t lie though – for Glenda’s book, a poor grasp of history hasn’t been the terrible impediment you’d expect. After all, her characters don’t know history either.

There is a face I make when I try to understand the past, and in particular when I’m in a conversation where I’m supposed to know something about it: my eyebrows shoot directly up in preparation of imminent understanding, and my lips stay still in a bluff of having understood, and between them my eyes shimmer with weird panic. I’ve tried my very best to capture that same face when drawing the characters in Once a Shepherd as Cherry, Tom and the stranger become swept up in the sludge and death of that unreasonable war. I like to imagine that they struggled to fathom the order of events as well.

So … the panicked expression of sad bluffing incomprehension? I made the same face the moment Sarah Foster from Walker Books Australia asked me to illustrate Once a Shepherd. Aaaaaaaagh! For  starters, I was utterly new at this. I’d only just begun to get serious about illustrating during the previous year, and besides flunking out of art school after a semester, I was completely self-taught and again, completely out of my depth. More than that though, Glenda was already a personal hero of mine. The Naming of Tishkin Silk is my very favourite book, and certainly the one that reignited my love for children’s books as a grown-up adult person; it makes me cry every time I read it. So what I’m getting at is, it’s a pretty scary thing to illustrate a book for one of your heroes. But we’ve emailed back and forth since the book has come out, and with every email it has become clearer that Glenda is among the most wonderful human beings alive.

starters, I was utterly new at this. I’d only just begun to get serious about illustrating during the previous year, and besides flunking out of art school after a semester, I was completely self-taught and again, completely out of my depth. More than that though, Glenda was already a personal hero of mine. The Naming of Tishkin Silk is my very favourite book, and certainly the one that reignited my love for children’s books as a grown-up adult person; it makes me cry every time I read it. So what I’m getting at is, it’s a pretty scary thing to illustrate a book for one of your heroes. But we’ve emailed back and forth since the book has come out, and with every email it has become clearer that Glenda is among the most wonderful human beings alive.

I struggled to find the right tone at first. During the initial storyboarding, I was aiming for the same caustic sarcasm as the war literature I grew up with: I’d skipped Biggles and gravitated towards Heller and Vonnegut and I so much wanted to ape their style of satire with my drawings. But the tone was a poor fit for Glenda’s writing. Here, there was no ironic barrier between the reader and her deep well of empathy and love, and I was really blowing it for a while there. The wonderful Donna Rawlins (designer) and Sue Whiting (editor) steered me very gently off this path and onto the far more empathetic book as it exists now. It seems obvious in hindsight, but at the time I hadn’t realised the possibility and importance of an anti-war statement that doesn’t disrespect the memory of the people caught up in that terrible machine. That’s something I thought about a lot over the year it took to paint the book, and it became a guiding principle – to paint from a place of human understanding. I still don’t know the first thing about World War One, but working on Glenda’s text, I’ve learnt about grief and loss and time and forgiveness and, to my mind, that seems like a very fine place to begin a conversation about it.

Half the week, I paint stories for kids written by people I lionised and loved when I was a kid. And the other half, I’m actually a children’s bookseller, talking to kids about the writers and artists that they lionise and love. I struggle to fathom the order of these events too, but it has been awesome and amazing.