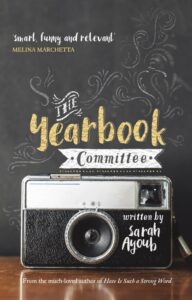

Sarah Ayoub’s new book The Yearbook Committee will be released on February 29th. We asked Sarah what the book means to her, and her insightful and thoughtful response challenges us to consider the notion of diversity, and how we, as readers, view authors and their subject matter. The Yearbook Committee is a powerful novel, one teenagers are sure to embrace. Thank you Sarah for your words.

Sarah Ayoub’s new book The Yearbook Committee will be released on February 29th. We asked Sarah what the book means to her, and her insightful and thoughtful response challenges us to consider the notion of diversity, and how we, as readers, view authors and their subject matter. The Yearbook Committee is a powerful novel, one teenagers are sure to embrace. Thank you Sarah for your words.

In a matter of days, I will launch my second novel, The Yearbook Committee, out into the world. It’ll be interesting to see how it will be received. By most accounts, it is starkly different to my debut novel, Hate is such a Strong Word. My debut’s storyline was heavily influenced by my personal experiences, and its protagonist was an Australian Lebanese girl living in Bankstown and attending a mono-cultural school. My second one follows the story of five very different year 12 students – male and female – as they’re forced to work on their school yearbook together at a posh private school in Sydney’s inner west.

When I first announced the book, there was the assumption that I’d be writing about Australian kids of non-English speaking backgrounds again. In fact, I’ve already received criticism for writing characters that are – at least on the surface – predominantly White. Maybe it’s because I am not ‘White’. Maybe it’s because I am a big advocate for diversity in the arts and in pop culture. Maybe it’s because we’re taking this need for diversity in books to whomever we can take it to, in a bid to share stories that more accurately reflect our widely diverse population.

Such expectations, while well-intentioned, can be a little daunting. They’re daunting because as an author, you already have a lot of responsibility on your shoulders. If you’re a bookworm you’ll understand – books are great shapers of thought, opinion and world views, and reading a great one is akin to a personal transformation. When you’re writing about teenagers in particular, you want to stay as true as you can to their personal experiences, and you don’t want anything that would take away from them. You want the stories you write to be authentic and relatable, and you want them to honour the characters you’ve imagined, particularly when they’ve shared their life with you.

Which is why, in a sense, writing Hate is such a Strong Word was easy – because it was real, and authentic and true. And I was glad that when it came out, a lot of readers loved it. But overall it didn’t create much of a splash. I got a lot of comments that suggested it was a ‘been there, done that’ kind of story. The implication was that we’d already had many coming of age stories where the protagonist was from a non-English speaking background that Sophie’s story – despite its point of difference being the mono-cultural school – wasn’t all that relevant anymore.

Which is why, in a sense, writing Hate is such a Strong Word was easy – because it was real, and authentic and true. And I was glad that when it came out, a lot of readers loved it. But overall it didn’t create much of a splash. I got a lot of comments that suggested it was a ‘been there, done that’ kind of story. The implication was that we’d already had many coming of age stories where the protagonist was from a non-English speaking background that Sophie’s story – despite its point of difference being the mono-cultural school – wasn’t all that relevant anymore.

Writing The Yearbook Committee was a whole other experience. This time, I wasn’t writing a story I lived. I was writing with the luxury that other authors have every time they put pen to paper (or fingers to  keyboard keys). I let creativity and experimentation take charge, and the result was a story that just happened to be about (mostly) white kids. And I didn’t want to change those kids – characters who I came to love – to prove a point. That said, I imagined – in my mind at least – that the feisty feminist Charlie was part-Indigenous. I just never felt like I had to write that into the story because her part-Indigenous heritage wasn’t something that influenced her role in the book.

keyboard keys). I let creativity and experimentation take charge, and the result was a story that just happened to be about (mostly) white kids. And I didn’t want to change those kids – characters who I came to love – to prove a point. That said, I imagined – in my mind at least – that the feisty feminist Charlie was part-Indigenous. I just never felt like I had to write that into the story because her part-Indigenous heritage wasn’t something that influenced her role in the book.

Writing the characters and their storylines was an organic process: there wasn’t a moment where I felt compelled to change who they were to satisfy a need for diversity. In fact, I like to think that I incorporated a little bit of diversity in a different way – while there wasn’t a big injection of truly ethnic-Australian characters, there were characters with Down Syndrome siblings and characters with no siblings. I had characters in nuclear families and characters in step-families, and characters in families were the parents weren’t present at all. I had characters who were well-off and a character who lived among housing commission flats on a highway in the south-west, who was quite content to remain friendless in high school, bar his one Palestinian friend from their former high school.

As an author, I remain committed to diversity and to encouraging, publishing and promoting the work of writers and artists of diverse backgrounds. But I never want this to be a token diversity – a ‘plonk in the ethnic’ scenario that exists to satisfy a set of criteria. Besides, how do these critics know that I didn’t pitch another ethnically-diverse book, only to be told that no publisher would be interested in it (again, in that ‘been there, done that’ kind of attitude)?

I write because it gives me the freedom to step outside the confines of my daily life. So I don’t want to pigeon-hole myself. I want to write about all sorts of people and experiences and settings, because to me, there’s a lot more to diversity than multiculturalism. And there’s a lot more to authors of foreign heritage than the colour of their skin, the food on their table or the experiences they faced because of their otherness.

Writers of foreign heritage have a right to be creative also – to work outside the box that they have known their whole lives. I hope people who pick up The Yearbook Committee will give it a chance – and look at it for everything that it is, instead of everything that it’s not.